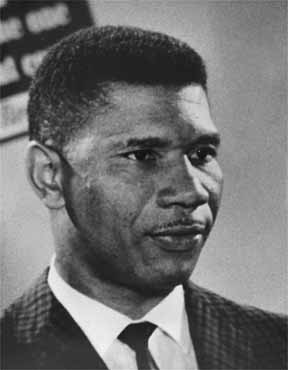

Medgar Evers, field secretary for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), was one of the first martyrs of the civil rights movement. His death prompted President John Kennedy to ask Congress for a comprehensive civil-rights bill, which President Lyndon Johnson signed into law the following year.

The Mississippi in which Medgar Evers lived was a place of blatant discrimination where blacks dared not even speak of civil rights, much less actively campaign for them. Evers, a thoughtful and committed member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), wanted to change his native state. He paid for his convictions with his life, becoming the first major civil rights leader to be assassinated in the 1960s. He was shot in the back on June 12, 1963, after returning late from a meeting. He was 37 years old.

Evers was featured on a nine-man death list in the deep South as early as 1955. He and his family endured numerous threats and other violent acts, making them well aware of the danger surrounding Evers because of his activism. Still he persisted in his efforts to integrate public facilities, schools, and restaurants. He organized voter registration drives and demonstrations. He spoke eloquently about the plight of his people and pleaded with the all-white government of Mississippi for some sort of progress in race relations. To those people who opposed such things, he was thought to be a very dangerous man. "We both knew he was going to die," Myrlie Evers said of her husband in Esquire. "Medgar didn't want to be a martyr. But if he had to die to get us that far, he was willing to do it."

In some ways, the death of Medgar Evers was a milestone in the hard-fought integration war that rocked America in the 1950s and 1960s. While the assassination of such a prominent black figure foreshadowed the violence to come, it also spurred other civil rights leaders--themselves targets of white supremacists--to new fervor. They, in turn, were able to infuse their followers--both black and white--with a new and expanded sense of purpose, one that replaced apprehension with anger. Esquire contributor Maryanne Vollers wrote: "People who lived through those days will tell you that something shifted in their hearts after Medgar Evers died, something that put them beyond fear.... At that point a new motto was born: After Medgar, no more fear."

“It may sound funny, but I love the South. I don’t choose to live anywhere else. There’s land here, where a man can raise cattle, and I’m going to do it some day. There are lakes where a man can sink a hook and fight the bass. There is room here for my children to play and grow, and become good citizens—if the white man will let them....”

—Medgar Evers, “Why I Live in Mississippi”

His death was a foreshadow of the violence to come...

(this is from Court TV, the language is a bit stilted, but it gives you the history of that day)

It was called "Bombingham." And the title was not meant to be funny. Things were so bad in Birmingham, Alabama, during the early 1960s, that everyone, black or white, risked their lives just by walking through the city's streets. A bomb could go off at anytime. From 1950 to 1960, dozens of bombings were committed in Birmingham by unknown terrorists. Black homes or businesses were usually the targets of these explosions. In most cases, the victims were alleged to have committed an offense against the rigid structure of white supremacy. This type of transgression, which disturbed the fragile throne of white privilege, was considered so serious that a man could pay for it with his life. To live in certain areas of the South during this time, a person had to accept the fact that the animosities of past generations were still very much alive and the frightening rule of white supremacy dominated the course of everyday life.

This is the story of one of the most infamous crimes of 20th century America, the bombing of a church during a Sunday service, which left four innocent teenage girls dead. The men responsible hid behind the cloak of secrecy, intimidation and the white robes of the oldest terrorist organization in the world, the Ku Klux Klan. For the last 40 years, this epic pursuit of justice, which spanned eight Presidents, inched forward to a bitter end, while the aging families of the victims looked on in patient anguish. But the terrible bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on September 15, 1963, will never be forgotten.

Its significance was nothing less than to alter the course of history and stir the conscience of a nation.

Still, they killed Civil Rights workers in 1964...

In Mississippi, in the 1960s, when segregation was king, racism the status quo, and bigotry the law, it was young people who rose up and challenged the system. In racially segregated and economically depressed Neshoba County, Mississippi, it was the local black youth and northern volunteers who challenged racism and led the fight for freedom and justice. Because of the sacrifices made by many people, most of the obvious signs of racism and bigotry have been eliminated. Because of the brutal beatings suffered by demonstrators at the hands of segregationists, public facilities have been desegregated.

To achieve the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, many marched, demonstrated, and suffered brutal beatings. And some died. For three who died, Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman, we still continue the struggle for justice.

On August 28, 1963 (only three weeks before the Birmingham bombing) Martin Luther King spoke on steps of the Lincoln Memorial. It has become known as his "I Have a Dream" speech. In it he said:

To say 1963 and 1964 were turbulent years would be an understatement. It was a time that caused a generation of young people to become deeply engaged with their country and its politics. It challenged us to soul-search, to take a side, to have an opinion, to question authority even when it was up close and breathing down your neck. The Civil Rights Movement reminded America of its greatest promises, and demanded that those promises be kept. On a very personal note, my cousin Harvey who died in 2001, internalized the dream and was a Civil Rights worker in 1963. He traveled to the south, hid in houses, got down on the floor when bullets flew from drive-by racists, and risked his life to register voters. And the pirate's ex-wife's brother-in-law also went south in 1963 to work for the Civil Rights Movement and was never seen again. I am a Jewish woman who lost family in the ovens at Auschwitz, so I have said with great intimacy, passion, and conviction: Never Again. I believe it is eerily apropos to utter these same words now --Never Again. We have a dream.

"...go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair. I say to you today, my friends, that in spite of the difficulties and frustrations of the moment, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream..."

No comments:

Post a Comment